Voxel raycasting

Voxels are great! Working in medical imaging, I encounter voxels on a daily basis. The medical images I work with are mostly volumetric data represented by voxels. Given the simplicity of voxels (think pixel, but in 3D), they are easy to work with for a lot of things. Now, one of the things I do is visualization of these images, such as rendering of a volume through raycasting. With that said, this post is not about medical visualization, the visualization I want to write about is more the kind you would see in video games.

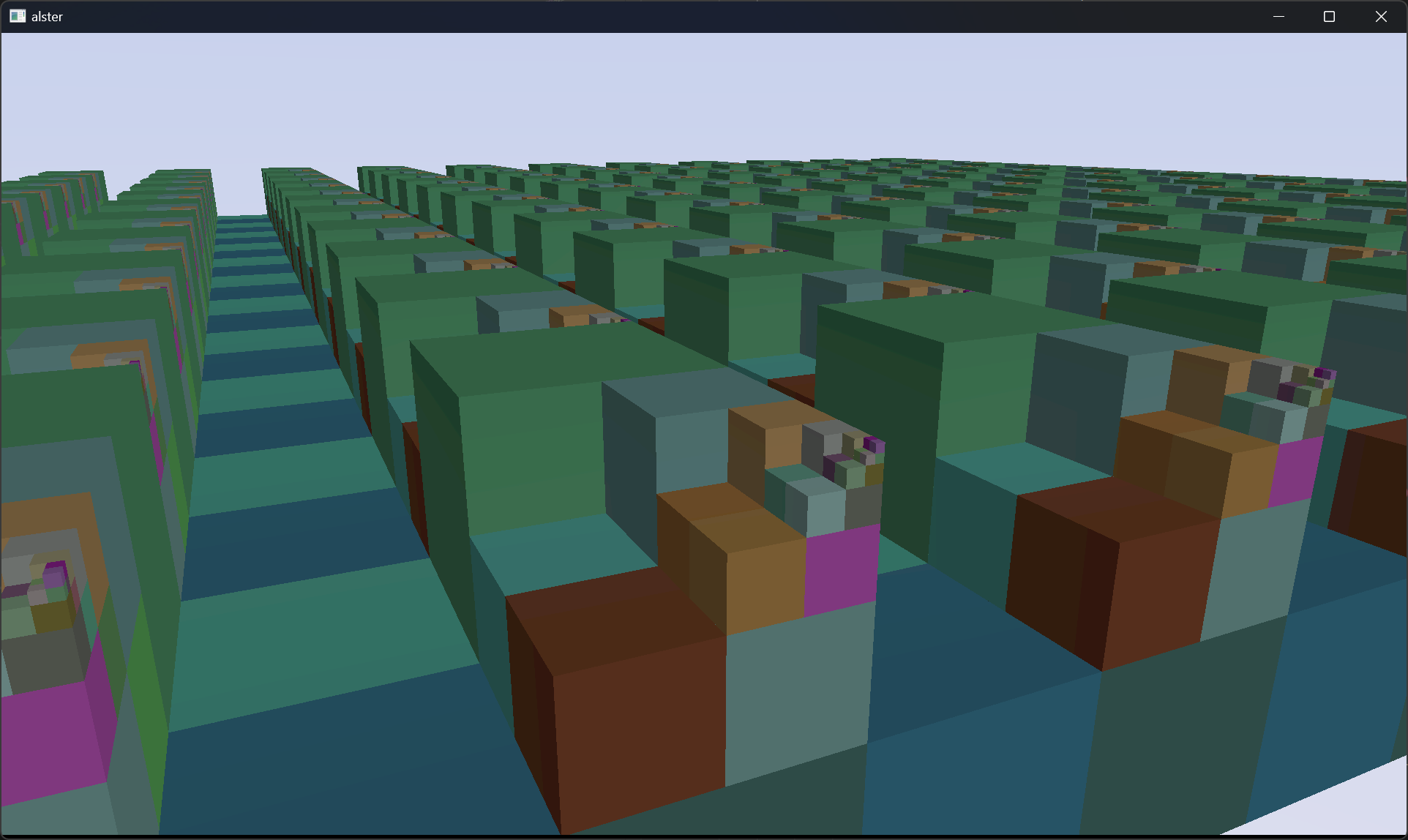

Maybe the most noteable example of using voxels in a video game is Minecraft. Here voxels are used to represent the world and it even allows for a very intuitive way of modifying the whole world. There are also cool tools for making art with voxels, such as MagicaVoxel, and if you search for something like “voxel rendering” on youtube you will find a lot of cool project showcases. Something I wanted to dig more into was the rendering of these voxels, especially with this typical voxel style (visible cubes).

Minecraft uses voxels for representing the world but for the actual rendering it actually converts visible voxels into triangles, which are then rendered more traditionally. Since Minecraft has quite large voxels, it is not really a problem to do it this way. Another approach for rendering these is called raycasting, and this happens to be the same approach I might use for my medical images.

Now, before getting too deep into the rendering, voxels are great but they can be a bit troublesome. Voxels are by defintion a dense representation, compared to the triangle-based approach where you only care about the surface of objects. This means that a region of the size 1024x1024x1024, which might not be much depending on your resolution, equals to over a billion voxels. Say that each voxel hold as little as 8 bits for coloring, that is 1 GB of data.

The problem is not limited to the actual storage requirements either. To be able to accurately raycast a scene, you need the ray to step a maximum of one voxel for each iteration. This means that very large volumes involves a lot of stepping, each step requiring you to actually sample the volume to determine if it is a hit.

Luckily, both these problems can be overcome by using something like a Sparse Voxel Octree (SVO). This means using a more sparse representation of our voxels, essentially encoding large areas with identical voxels (such as air) into a more compact representation. It also happens that these can be efficiently traversed when doing raycasting as well, as presented by Laine & Karras [1]. I will not go into too much detail here about the actual structure since I still have a few things to decide on. There are even more approaches for representing the data such as Sparse Voxel DAGs (Directed Acyclic Graphs) [2] or Hash DAGs [3]. However, the traversal algorithm is very similar for all these cases so this should do for now.

Raycasting

Putting any complex representation of our voxel data aside, lets consider a simpler case. Given a volume consisting of NxNxN voxels we want to render this volume using raycasting. The first thing we want to do in our shader is to define a ray that goes from the camera into the volume. Given that I am using the game engine Bevy, I already had my projection and view setup so I just computed the ray origin and ray direction for each pixel using the already existing view parameters. Note that all code I provide below is written in wgsl.

let ndc = uv * 2.0 - 1.0;

let cs = vec4<f32>(ndc.x, -ndc.y, 1.0, 1.0);

var vs = view.inverse_projection * cs;

vs.x /= vs.w;

vs.y /= vs.w;

vs.z /= vs.w;

vs.w = 0.0;

let ray_dir = normalize((view.view * vs).xyz);

let ray_origin = view.world_position;

Now the core part of the raycasting algorithm is a loop that steps through the volume. A naive approach here might be to just step at a fixed interval, but this might not only be slow if a lot of unnecessary steps are performed, it also has a tendency to produce artifacts. A better approach is to use the DDA-based algorithm such as the one presented by Amanatides & Woo [4]. These approaches, as illustrated above, ensures the ray traverses voxels one by one. A fun read on using DDA for Wolfenstein 3D like rendering can be found here.

var pos = (ray_origin + ray_dir * t_start); // t_start: distance to start of volume

var map_pos = floor(pos)

// Distance along ray from one x or y side to the next.

let delta_dist = 1.0 / abs(ray_dir);

let step = sign(ray_dir);

// Distance along ray from current position to next x or y intersection

// Slightly simplified from lodev to avoid big if/else section

var side_dist = (rd_sign * (map_pos - pos) + 0.5 * rd_sign + 0.5) * delta_dist;

// Current distance along ray

var t = t_start;

var mask = vec3<f32>(0.0);

while t < t_end {

// Check for hit

if is_hit(map_pos) {

break;

}

// Step

// Here we want to pick whatever intersection is the closest, since side_dist

// provides the distance to each side we pick the smallest value.

mask = vec3<f32>(side_dist.xyz <= min(side_dist.yzx, side_dist.zxy));

// Compute the new distance

t = dot(side_dist, mask);

// Update distances

side_dist += mask * delta_dist;

// Update position

map_pos += mask * step;

}

Raycasting a hiearchy

We now have a way of raycasting a volume with only uniform voxels. Now, lets move that into actually traversing an octree hiearchy. The core principle is the same, step through the volume voxel by voxel, but extra care need to be taken to ensure we follow the hiearchy.

This implementation is very similar to the one presented by Laine & Karras [1] with a some simplifications. One major difference is that rather than keeping a stack of nodes when traversing the hiearchy, I have opted for returning to root after each step to make things simpler. I yet have to evalute the potential performance trade-offs but this is what I threw together to get started with.

The data structure used in this case is a simple SVO and starts of with a root node in the first level (l=0). It then continues as a typical octree, second level contains at most 8 nodes, etc. Any node without children is considered a leaf node, holding a single voxel of size (CHUNK_SIZE / 2^l) (in each direction). Each node consists of 2x uint32, one with the child index and one with a material value, basically marking its color. Nodes are just stored in a linear array and accessed through their index. As in the paper, all children of a node is stored next to each other, so a parent just points to the first child node.

let pos = ray_origin + ray_dir * t_min;

let inv_dir = 1.0 / abs(ray_dir);

let rd_sign = sign(ray_dir);

// Will be initialized later

var node_id = 0u;

var material = 0u;

var voxel_size = 0.0; // Current voxel size

var node = Node(0u, 0u);

var map_pos = vec3<f32>(0.0);

var side_dist = vec3<f32>(0.0);

var step_mask = vec3<f32>(0.0);

var child_mask = vec3<bool>(false);

// Current distance along ray

var t = t_start;

while t < t_end {

// Go to root of octree

node = get_node(0u);

voxel_size = CHUNK_SIZE;

// Position within the current node (root)

// Assuming t_start and t_end are correct we should hopefully never end up

// outside the volume.

map_pos = (pos + ray_dir * t) % voxel_size;

// Go as deep as possible in the tree

// I.e. until we hit a leaf node

while node.children != 0u {

voxel_size *= 0.5;

// Determine what child we are currently in

child_mask = map_pos >= voxel_size;

node_id = node.children + u32(child_mask.x) + u32(child_mask.y) * 2u + u32(child_mask.z) * 4u;

node = get_node(node_id);

// Update map_pos to keep it in range [0, voxel_size]

map_pos = map_pos % voxel_size;

}

// Check node content

if node.value != 0u {

// Not air

material = node.value;

break;

}

// Step to next voxel at current level

side_dist = (rd_sign * (-map_pos) + 0.5 * rd_sign * voxel_size + 0.5 * voxel_size) * inv_dir + t;

step_mask = vec3<f32>(side_dist.xyz <= min(side_dist.yzx, side_dist.zxy));

t = dot(side_dist, step_mask);

}

Now there are probably a lot of improvements to be made, for instance to avoid artifacts due to floating point precision issues you might have to adjust t in certain areas. But for now I feel this is a good starting point. Next step is to look more into how to structure the data and how to efficiently feed it to the GPU.

References

| [1] | Laine, Samuli, and Tero Karras. “Efficient sparse voxel octrees.” Proceedings of the 2010 ACM SIGGRAPH symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics and Games. 2010. |

| [2] | Kämpe, Viktor, Erik Sintorn, and Ulf Assarsson. “High resolution sparse voxel dags.” ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 32.4 (2013): 1-13. |

| [3] | Careil, Victor, Markus Billeter, and Elmar Eisemann. “Interactively modifying compressed sparse voxel representations.” Computer Graphics Forum. Vol. 39. No. 2. 2020. |

| [4] | Amanatides, John, and Andrew Woo. “A fast voxel traversal algorithm for ray tracing.” Eurographics. Vol. 87. No. 3. 1987. |